Sometimes a news story strolls out of the “peculiar events” category and lands squarely in territory that feels, if not surreal, then at least distinctly improbable. Such is the saga unfolding from a West Bank crocodile farm—an ill-fated enterprise now in the news for a final, sobering solution to a problem it couldn’t contain.

Crocodiles Out of Place (and Out of Patience)

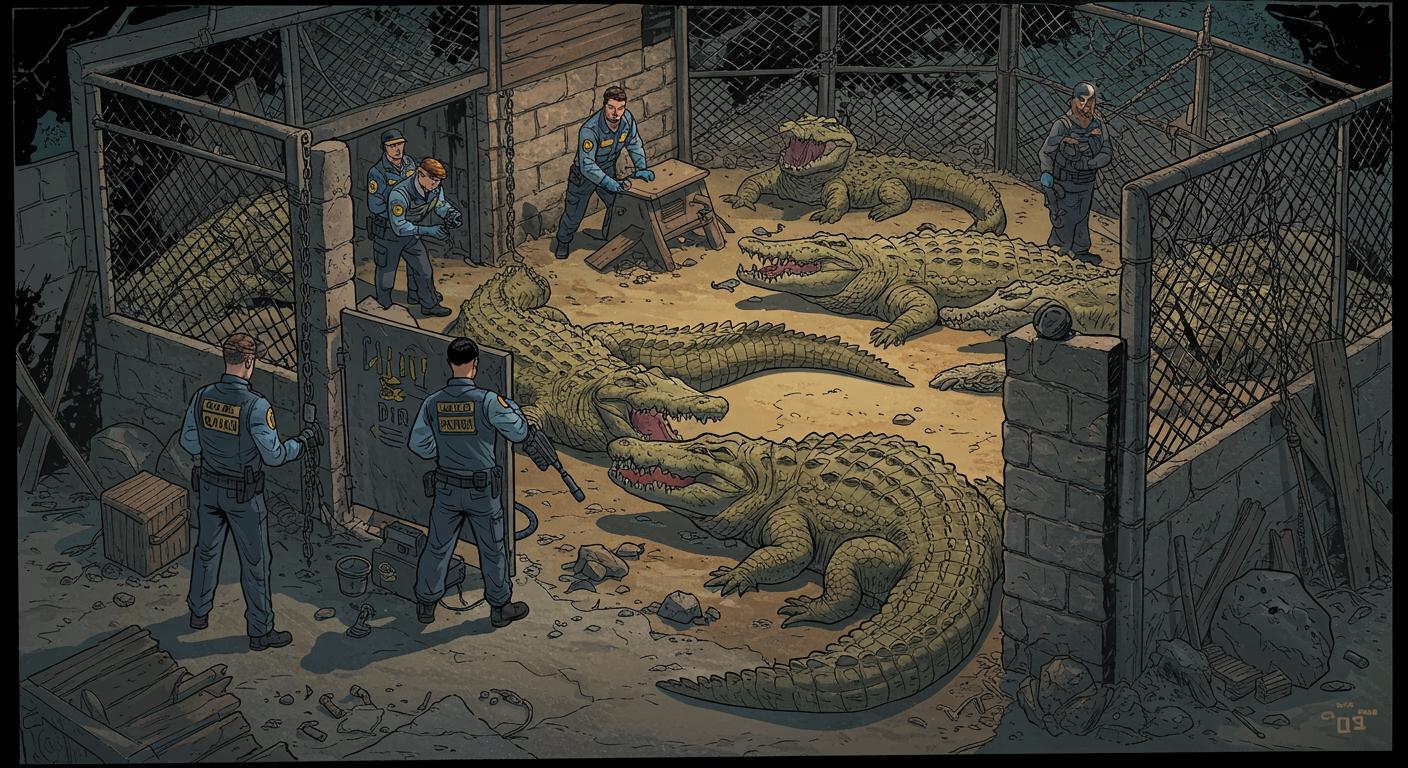

Described in the Associated Press, it all began decades ago, when a “bask” (one of English’s more evocative animal group names) of crocodiles was imported to Petzael to jumpstart a local tourism industry. But regional violence quickly scuttled visitor numbers, prompting a handover to an entrepreneur who—with a certain optimism—aimed to sell crocodile skin. Expecting the business to rebound probably seemed ambitious, but legislative change soon closed the door for good: Israeli law in 2012 classified the reptiles as protected animals, banning their sale for meat or merchandise. Since then, the crocodiles’ future has hovered awkwardly between historical footnote and headline risk.

That’s an odd trajectory, even among niche animal ventures. One almost has to admire the initial bravado: crocodiles, billed as family entertainment, parked precariously close to the Jordan River and, by extension, an international border. In a detail highlighted by the AP, the head of the local community reflected back in 2018, “I don’t want to think of what will happen if a crocodile manages to escape and reaches the Jordan River, and then we’ll have an international incident.” The border is just 4.2 miles away. Surely, there are less anxiety-inducing mascots for cross-cultural exchange.

The Great Reptile Breakouts

Years of neglect and periodic escape attempts have haunted this abandoned farm. Officials told AP that the compound had closed in 2013 and fallen into such disrepair that basic conditions deteriorated. COGAT, the Israeli defense body overseeing these matters, stated the Nile crocodiles not only lacked proper food but, in a persistent state of hunger, had even turned cannibalistic.

Earlier in the report, it’s mentioned that authorities invested more than 100,000 Israeli shekels (exceeding $29,000) in efforts to re-fence the property. Yet, that did little to address recurring reports of crocodiles eyeing the boundaries and, on at least a few occasions, making their way beyond them. The outlet also notes that as these breakouts continued, the risk of a wandering crocodile stirring up diplomatic drama (or at least regional panic) grew much less hypothetical with each incident.

Humane Ends? Or Just the End?

In response to this unsolvable puzzle, authorities ultimately decided on a drastic course. COGAT asserted, in details relayed by the AP, that government veterinarians were brought in to cull the crocodiles, citing an untenable mix of animal welfare failings and public safety threats. While the exact tally of euthanized animals and the particulars of the procedure remain unreported, officials emphasized that veterinary guidance played a role in the method chosen. The narrative of the farm’s rapid decline from tourist trap to humanitarian crisis is unsettling—though its logical conclusion, given such a set-up, feels inevitable.

Reflections on an Odd Saga

It’s tempting to treat this as another lesson in the perils of combining entrepreneurial optimism with unpredictable wildlife. Yet, there’s something striking about how the story’s weirdness accumulates—neglected crocodiles, escape artistry, abandoned commercial ambition, and a final act that’s both tragic and, in hindsight, curiously foreseeable.

What stands out most, though, might be how little it takes for the improbable to become an administrative headache: a few fences, a lapsed maintenance schedule, and suddenly the possibility of a cross-border crocodile incursion is keeping officials awake at night.

Are we truly surprised that crocodiles refused to quietly accept a fate crafted by human planners? Or is the real marvel that anyone expected them to? In the end, perhaps the oddest twist is that this story ever had to be written at all.