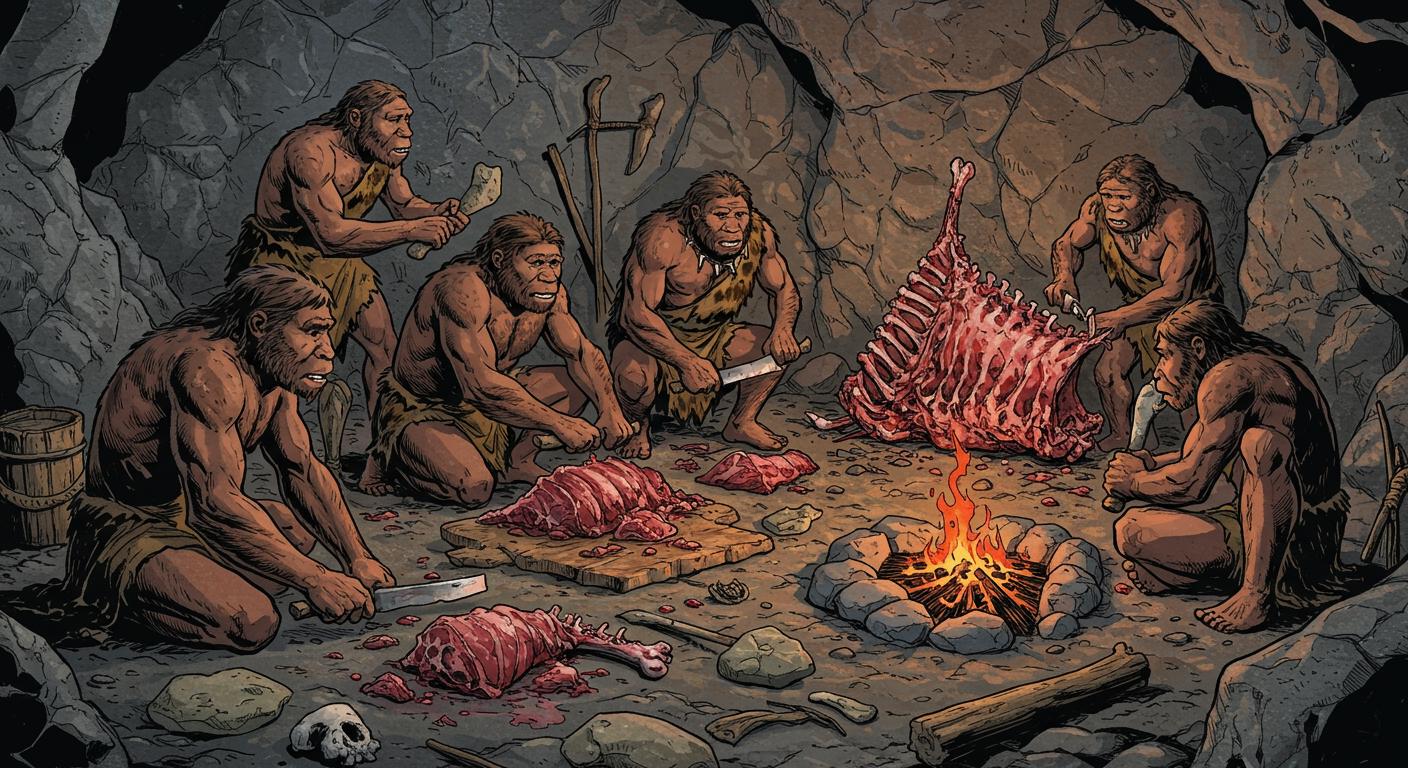

Let’s face it—if most of us picture our distant cousins, the Neanderthals, we don’t immediately envision anyone laboring over artisanal charcuterie or debating the finer points of food prep. The tired trope is that they spent their days clubbing dinner into submission and eating it more or less as-is, possibly with a soupçon of cave dirt. But in a turn both oddly relatable and gently subversive, new research shared by NewsNation suggests Neanderthals weren’t simply eating to live—they were developing their very own culinary sub-cultures, with meat-preparing techniques that varied enough to hint at group-specific traditions.

Cut Marks and Culinary Traditions

As laid out in the NewsNation report, archaeologists analyzed 344 animal bone fragments from two neighboring cave sites in present-day Israel, both occupied by Neanderthals. Though the caves—Amud and Kebara—were close together geographically and the Neanderthals there had similar tools and access to the same types of game, researchers noticed distinctive butchery patterns on the bones from each site.

Study authors, in a passage highlighted by NewsNation, concluded that these subtle discrepancies in cut marks “could possibly reflect inter-group cultural differences related to carcass processing preferences, organization of tasks within the group, or socially transmitted traditions.” In other words, even with nearly identical conditions, the two groups evolved their own approaches to the butcher’s craft. Was it a matter of taste, efficiency, identity, or just the stubborn perpetuation of “the way we’ve always done it”? The evidence doesn’t offer recipes, but it does indicate some very ancient culinary habits.

Not Just Survival—Style

The outlet also notes the broader implication: where modern humans might feud over pizza styles or barbecue technique, Neanderthals seem to have developed personal spins on how to get from carcass to cutlet. Since environmental and technological factors were so similar between the two cave-dwelling groups, the researchers argue these differences likely emerged from tradition—not necessity. It’s a quietly radical notion: rather than surviving on brute instinct alone, these individuals were passing down butchery strategies, perhaps critiquing and iterating on them over countless generations.

Earlier in the report, it’s mentioned that food is often a key marker of cultural boundaries in contemporary societies. That notion seems to carry backward, as the study finds even Neanderthals “formed their own sub-cultures, similar to today.” You have to wonder—if one group had a preferred method for marrow extraction, did the neighbors scoff in cave-kitchen solidarity, or did the techniques quietly blend over time?

A Flare for the Familiar

It’s easy to caricature these ancient cooks as grim optimizers, but perhaps the reality—supported by the delicate work of cut marks—was more nuanced. Even in settings defined by sameness, humans (and apparently Neanderthals, too) find ways to distinguish “our way” from “theirs.” Whether by proprietary brisket rubs or, as NewsNation describes, distinct cut marks on prehistoric bones, the impulse to mark cultural identity seems as old as the species themselves.

Does this mean your love for a particular family recipe is rooted less in flavor and more in ancient patterns of social cohesion? Or that our dinner-table quirks are echoing something bone-deep and surprisingly communal? The study doesn’t claim Neanderthals gathered to discuss the finer points of seasoning—but it does leave us with the image of a lineage that found meaning, and maybe a little pride, in the everyday act of preparing food. The proof, it seems, is still visible to anyone with a sufficiently sharp (and well-attributed) lens.