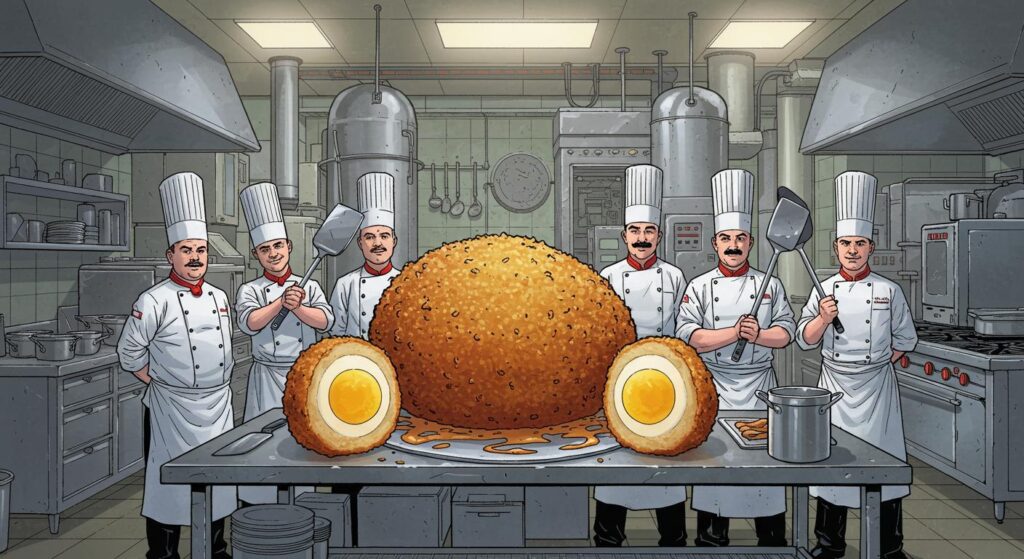

In the ever-expanding annals of governmental micromanagement, Belarus has added a new, distinctly starchy entry: grocery stores can now be penalized for failing to keep potato supplies robust. As TVP World describes, President Alexander Lukashenko’s most recent regulation means fines of up to €2,200 now await retailers and wholesalers if their potato inventory falls short. One wonders if inspectors use a ruler or just a knowing glance to determine what amounts to an egregious lack of spuds.

A Crisis in a Sack

Amid what TVP World characterizes as an “apparent potato crisis,” staple supplies have reached the point where scarcity and lackluster quality occupy equal footing. The potato, unofficially venerated as Belarus’ national vegetable, suddenly finds itself protected by law—scarcity is seemingly as much a societal faux pas as a supply-chain hiccup. The regulation, which became official with Lukashenko’s signature last Saturday, shifts responsibility squarely onto markets and suppliers, requiring their shelves to stay reasonably stocked, especially when harvests are lean and appetites apparently are not.

But why are potatoes suddenly so elusive in a country that holds them in nearly mythic regard? The explanation, detailed by TVP World, is a classic case of unintended consequences: the government capped retail prices in an effort to keep spuds accessible. The result? For many farmers, exporting potatoes to neighboring Russia—where prices are reportedly twice as high—has proven far more lucrative. With their best produce heading east, it appears stores back home are left to offer the leftovers, often of questionable quality. Economic logic, it seems, will always find a side door.

Regulatory Loops and Loan Offers

Feeling the tuber-shaped pinch, the government’s solution has been to double down on intervention. TVP World notes the introduction of an “anti-deficit” decree, allowing shops to take out low-interest loans—essentially putting money up front for future potato, carrot, or cabbage deliveries. Whether this financial maneuvering brings a bounty of fresh produce or simply rearranges empty shelves is anyone’s guess. And for grocers, a missing heap of potatoes is no longer a mere restocking issue but a matter of legal compliance—an escalation not many grocery managers likely anticipated when they signed up for the job.

More Than Just a Vegetable

President Lukashenko’s personal background as a former collective farm boss may help explain his focus on potato policy. As TVP World notes, he’s been openly critical of both supermarkets and his government over this supply shortfall. Is this the nostalgia of an agrarian past, or just a very dogged approach to national staples? Belarus’ new fine-centric approach places the humble potato in a strangely elevated position—half grocery item, half symbol of civic duty.

It raises some odd questions. What standard determines “enough” potatoes? Will Belarusian state inspectors develop an intuitive sense of potato scarcity, or is this destined to become another exercise in bureaucratic hairsplitting? In a country where fines await the under-stocked, one can only imagine the creative explanations grocers might devise—or what might count as extenuating tuber circumstances.

The Cycles of the Spud

Taken together, these measures seem less an isolated episode and more a chapter in the perennial story of state-planned economies chasing their own logic. As TVP World documents, attempts to control price and supply have a way of looping back to create new shortages—today with potatoes, tomorrow perhaps with some other root vegetable. There’s an odd comfort in the predictability of it all.

Perhaps future historians will mark Belarusian decades not by artistic movements or political cycles, but by the potato quotas mandated on supermarket shelves. In this corner of Europe, for now at least, a full sack is now as much a legal requirement as a culinary one. Is this the only country where grocery shopping can become a civic obligation—with potatoes at its core? In Belarus, it certainly appears so.